Bear Witness

If you find yourself in downtown Frederick, Maryland, take a detour to the corner of Council and Record Streets. Standing there, you look over City Hall Park, once known as Court Square, one of the most historically rich locations in the city. Imagine a half-century of activity in this spot, starting at the founding of Frederick Town in 1745. Fast-forward through time, and you will witness the building of Frederick County’s first courthouse in 1750, observe the construction of the town’s first jail three years later, and engage in the clamor during one of the first colonial acts of rebellion – Frederick’s 1765 Stamp Act protest. Steel yourself on Christmas Day, 1777, as one hundred Revolutionary War prisoners attempt an escape by setting the jail on fire, then witness the erection of the second courthouse in 1785, where brothers-in-law Francis Scott Key and Roger Brooke Taney practiced law before they both gained national prominence.

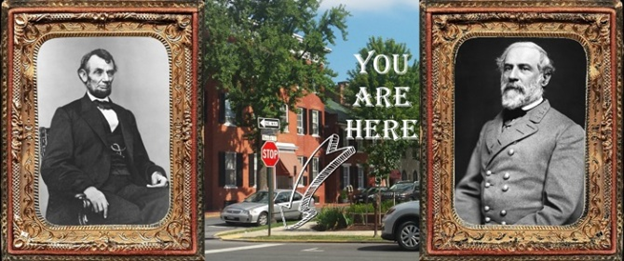

Pause here, in 1817, and gaze down Council Street. Identical neighboring houses are erected on the former jail site by John Brien and his father-in-law, Colonel John McPherson. One would come to be known as the Mathias (Brien) House. About three years later, a home on Record Street was erected just around the corner. Two homes now stand at Court Square that within weeks of each other will bear witness to visits from two of the most towering men of the Civil War: Lincoln and Lee.

It Is Now September, 1862

To the right of this photo is the Mathias (Brien) House on Council Street. On this corner in 1862, you could spot Confederate General Robert E. Lee entering the brick and wrought iron gate, heading up the marble stairs, and disappearing through the transomed door. He made this home his temporary headquarters for several days despite the cold reception of his army by the citizens of Frederick. In the days after Lee’s departure, Union General George McClellan moved his army through Frederick in pursuit of the rebels, and the following day Lee’s “Lost Order” 191 was discovered just three miles away from this home.

Lee and McClellan’s armies met in Maryland at the battles of South Mountain and Antietam, which ended Lee’s first invasion of Union territory. As the southern General turned his forces back to Virginia, Frederick would be overrun for months by wounded Union and Confederate soldiers reeling from the horrors of the Battle of Antietam, with the homes and churches surrounding Lee’s former headquarters serving as makeshift hospitals.

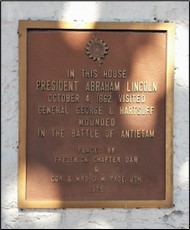

October 4, 1862

In the weeks after the Battle of Antietam, President Lincoln paid a surprise visit to General McClellan, still camped in the vicinity of Sharpsburg. On the president’s return trip to Washington he paid a visit to the home of Mrs. Ellen Ramsey, a mere 250 feet away from Lee’s former Frederick headquarters. Union Major General George L. Hartsuff, who was severely wounded at Antietam, was convalescing in the home on Record Street.

Lincoln entered Frederick under a vastly different banner of war than Lee. Two weeks earlier, following the single bloodiest day in American history, President Lincoln announced the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Lee’s defeat at Antietam gave Lincoln the opening he had waited for to make this declaration, marking a major turning point in the Civil War. Henceforth, the Confederacy would receive no aid from abroad, and the cause of the war expanded from maintaining the Union to include the abolition of slavery in rebel states. The 100 day countdown had begun, and the pressure on Lee to overtake the Northern Army was greater than ever.

Upon leaving the Ramsey’s house on Record Street, a crowd greeted Lincoln and begged for a speech. He made a short remark, then continued on his way along Court Street and down Market to the B&O Railroad Station (now the Frederick Community Action Agency). He addressed the fervent crowd gathered there, then stepped onto the train bound for Washington, waving his trademark hat.

This was not the end of Frederick’s role in the Civil War, but it was the conclusion of this unique moment in time around the Maryland Campaign of 1862, when the hazy line between North and South, embodied by Lincoln and Lee, passed over our border state in downtown Frederick on the corner of Council and Record Streets.

Related Items of Interest

Both the Ross and Mathias homes had extensive outbuildings. Some are still visible along the rear of the properties at 106-114 W. Second Street.

For several decades in the mid-1800’s, the Brien-McPherson families ran Catoctin Furnace and the Antietam Ironworks. The McPherson family also owned a farm and built the Gambrill Mill, both of which now reside within the boundaries of Monocacy National Battlefield.

Although appearing for only seconds, the Mathias and Ross houses are featured in the opening scene of the feature film, Gods & Generals. The Mathias (Brien) House coincidently plays background to another visit by Robert E. Lee, acting as a stand in for Washington D.C.’s historic Blair House. The scene’s interior shots were filmed at the Ross house next door.

David C. Winebrener purchased the Mathias (Brien) House in 1878. His great-grandson, Senator Charles McCurdy “Mac” Mathias Jr., who highway 270 is dedicated to, was born in the home. Senator Mathias repeatedly introduced bills during his tenure in Congress, asking for reimbursement to the City of Frederick for the ransom paid to keep Confederate Gen. Jubal Early from burning the town during the Civil War.

Image of Council Street by Art Anderson.